Honouring My Mother: Mary Frances Lillian “Billy” Gervais

Quiet Courage

Some stories live quietly in a lifetime—untold moments that slip between words, gestures, and memory. My mother’s story is one of them. It is a story mended like wool socks—knitted together by laughter and often darned in silence.

Her resilience and stubbornness were a mixture of brutal honesty that could be abrupt and unexpected. Comical and refreshing.

She was not perfect. She was human. And in honouring her, I want to tell not just who she was, but what she taught me about life, love, and the quiet courage of being present. No strings attached. The right place at the right time…how sometimes, we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

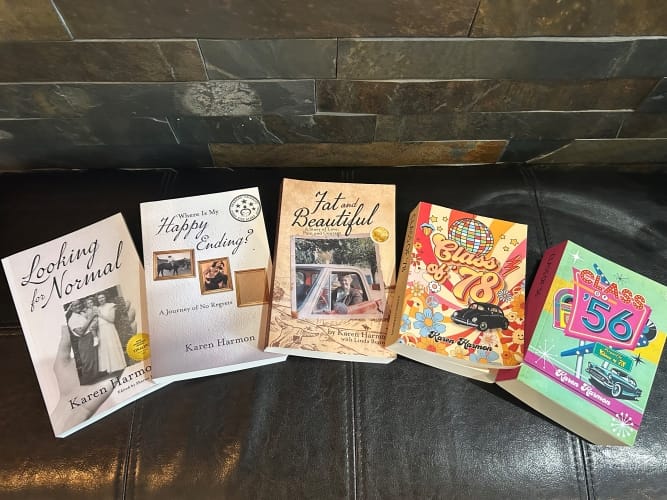

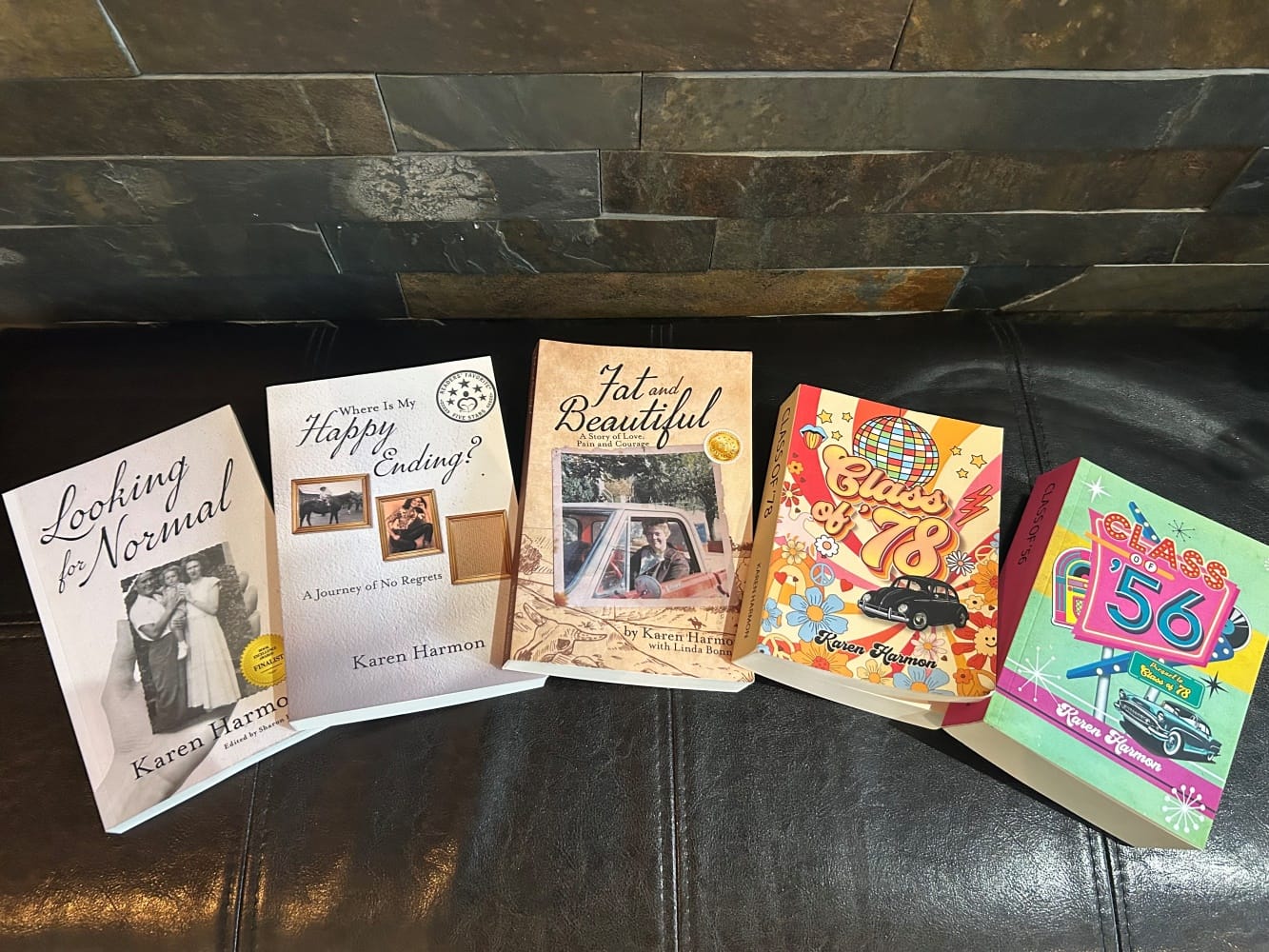

As some of you may know, my mother was a lovely woman, with a few quirks that sharpened with age. She was thirty-nine when I was born, making her a different kind of mother than the one my older siblings had. I didn’t realize it at the time—only after writing about her in Looking for Normal, did it become clear.

When she married at 25, my mother already felt old. Most of her friends had long since settled down, some with children already in school, and she worried she’d missed her chance. She was tall and thin—five feet ten and barely 120 pounds on her wedding day. Pale skin, blonde hair fading to brown, grey eyes that once held a softer blue. She often said she was shy and unphotogenic, but that wasn’t true. She stood out, whether she wanted to or not.

She always refused to get her picture taken. Maybe that’s why there aren’t many photos of her in this story. But I digress.

When I was small, she wasn’t a conversationalist. That was my father’s department. Growing up as the youngest, with my three older siblings out and occupied with school, Little League, horses, boyfriends, girlfriends, and other activities, there was very little talking around the house in their absence. I like to think I inherited a balance between my chatty father and quiet mother—enough to love quiet days, yet still start a conversation when I want to.

Yesterday, I told my son a story about his grandmother that he had never heard. Mary Frances Lillian Gervais had been nicknamed “Billy” by the father she adored. She told me proudly that she had been a bit of a bully—and I know that term feels heavy today—but for her, it was a badge of survival.

As a child, her life had not been easy. Her mother was cruel and favoured her firstborn, Violet. Together, they picked on Frances horribly. Her father adored her, but she never developed the mother-daughter bond she longed for. Instead, she found one with her best friend, Ruth, whose own mother had died.

When she told me the story of when she was a “bully,” it wasn’t with bitterness, but with a kind of private pride. It happened in early fall. In Tabor, Alberta, the onset of winter is crisp and fresh—orange and crimson drifting through the air, fields of dried corn stalks bowing under their own weight, and the ground hardened where sugar beets had been pulled. The cold settles in deep but carries the scent of harvest, of woodsmoke curling from chimneys.

She had grown weary of being chased. At first, it had been a game—a cat-and-mouse display of affection by some of the small-town boys. They would wait for Billy (my mother) and Ruth on their bicycles and chase them, hollering and carrying on as boys sometimes do. But she had had enough.

That autumn morning, Billy devised a plan. She found an old sock, probably darned into a bulging wool-mended mass, and stuffed it with small rocks. She left it outside in the prairie air to freeze overnight. The next day, as Ruth and Billy strolled home from school, they were ready. As the boys rounded a corner with taunts and threats, Billy swung that frozen sock over her head, Hercules style—and let it fly. The lead tormentor got a bloody nose. From that day forward, Ruth and Billy were never bothered again.

She told me that story often. For her, it wasn’t about cruelty—it was about standing up for herself and her friend. It was about quiet courage, the kind that doesn’t need anyone to notice.

For my siblings, she had been the perfect 1950s housewife. Roast beef with all the trimmings on Sundays, beef stew and soft homemade white bread on Mondays. Shirts ironed to perfection, bridge club at the house, and neighbours stopping by for “Open House,” carrying tiny sausages and white buns with tuna fish and one black olive from a can, placed strategically on top.

By the time I came along, the 1960s had slipped into the 1970s. Cake mixes, Tang, and cheese from a tube had found their place in our kitchen. My childhood carried a different scent—part convenience, part change. And in those years, my mother herself began to shift. She started talking more.

One morning, while she was ironing and half-watching Love of Life, she said it almost offhand, as if letting me in on a secret: “You know, I never really saw myself as a mother. I always had my nose in a book. I thought I might like to be a writer—or a private investigator.” Then, with the faintest smile, she added, “I had no idea what to do with a baby. Thank goodness for your father. I much preferred propping you up with cushions and a bottle so I could catch up on my reading.”

Her honesty stung, but it didn’t wound. If anything, it felt like an invitation into her private world—a side she didn’t show often. My father had been the one to wrap me in hugs and affection, but in her own way, she was giving me something just as rare—the truth of who she was. I think it was in those moments of confession that I learned to listen. Not just to words, but to what sits underneath them.

One afternoon she blurted out that she’d never wanted to call me Karen. It had been my father’s turn to choose—or maybe she just lost the energy to fight for it. If it were up to her, she said, I would’ve been Brook. She’d read the name in a book long before Brooke Shields made it famous, and it stuck with her.

Brook Bonner. Can you imagine it? Not exactly typical for the 1960s, but sharp, different, unforgettable. I used to lie awake wondering if a name could change a person. If I’d been Brook, would I have carried myself differently? Would my story have unfolded another way? Would I have stepped into the world with a different attitude or been more confidant?

Instead, I was Karen—one of five in my high school graduating class.

And yet, even now, decades later, I still catch myself daydreaming about it. That other name, that other version of me. It lingers, like a whisper from a life I almost had.

All these confessions, small tidbits, might have hurt. But in hindsight, it was another form of honesty—a crack in the mask of the “perfect housewife.” Historian Joanne Meyerowitz writes that in the 1950s, being the “perfect housewife” meant more than cooking and cleaning; it was about fulfilling a cultural ideal of emotional sacrifice and domestic devotion. (#1) My mother lived in two worlds: the dutiful homemaker of the fifties and the quietly resistant woman of the seventies. She never became the writer or detective she dreamed of—but she taught me that even the perfect housewife has cracks. And that’s where the real person shows through.

That real person began to show even more in the late 1970s. I was fifteen, and my mother had started to retreat. We had moved from North Vancouver—where my parents’ home was filled with laughter, business, bridge clubs, and open houses—to a log house on fifty acres in Mission, B.C. It was beautiful, but quiet.

Maybe, too quiet.

That’s when she began to slip. She lost weight, skipped meals, and spent hours sunk into the La-Z-Boy recliner, distant and withdrawn. My father noticed. When he pushed her to see a doctor, she was diagnosed with what was then called manic depression, now known as bipolar disorder.

Today, the condition is better understood—seen as a spectrum of mood disorders, each with its own patterns and challenges. Treatment often includes a mix of medication, therapy, and lifestyle support. Still, stigma lingers. And in the 1970s, it was even heavier. Women were expected to be caretakers, homemakers, the steady heart of their families. Stray from that role and you risked being dismissed as “hysterical” or morally weak rather than medically ill (#2) Treatments were blunt, support was scarce, and the weight of it all fell on the family.

For me, her diagnosis reshaped everything—our routines, our relationships, even the way I saw her. As the youngest, I was the only one left at home to witness it. My siblings were already gone, living their own lives, and I never really noticed or begrudged them for it. When her moods swung from low to high—zero to one hundred in seconds—I reacted the way teenagers do: annoyed, embarrassed, confused. It became the background noise of our home.

And then came my own storm. At fifteen, tangled in self-discovery, I crossed a line I wasn’t ready for—he was twenty-two. That’s another story. But in that moment, what I wanted most was my normal mother. Not a patchwork of Phil Donahue diagnoses and Oprah guests who seemed to have all the answers. Just her.

That label—manic depression—didn’t just define her condition. It cracked something open in our family. But it also revealed her quiet strength. She showed me that resilience doesn’t always roar. Sometimes it lives in small acts—showing up when it’s hard, telling your truth when no one asks, holding on to yourself when the world tries to box you in.

It’s the same resilience she carried as a girl, swinging a sock in defiance when life pressed in on her. Not loud, not showy, but hers. And it stayed with her, all the way through.

I share this in her honour, and as an invitation—to notice the quiet courage around us, to listen without judgment, and to hold people’s stories with care.

Later, she grew into the role of kooky grandma. She flat-out refused to date, and absolutely refused to remarry after my father died at seventy-one. She was sixty-six and unapologetic: “Men of my generation just want a maid—someone to cook, clean, and eventually change their diapers.” Harsh? Maybe. But I secretly loved having her all to myself.

We all grieved my father—he was the glue and spackle of our family. But in his absence, my mother somehow became the fun, the drama, the entertainment. Sometimes on purpose, sometimes without even knowing it. She admired Carol Burnett’s wit, Lucille Ball’s glamour and moxie, and Mary Tyler Moore’s brains and independence. In her own way, she lived somewhere between them all.

After someone dies, these stories shift. They’re no longer just memories—they become lessons. For me, hers wasn’t about defiance but a quieter kind of courage. The kind that doesn’t shout. The kind that shows up in small, stubborn acts: telling your truth, standing firm when no one’s watching, choosing to be yourself despite everything.

This October, as the air sharpens and the leaves flare, I remember her—Billy, my mother—the woman who taught me that strength comes in many forms, and that stories are how we carry it forward. And wouldn’t it be something—heartwarming and bittersweet—if Billy and Brook could sit down for a cup of tea, lean into the quiet, and reminisce? I imagine they’d laugh, maybe cry, and somehow find themselves right where they were meant to be.

And it makes me wonder: how often do we mistake someone’s sharp edges for meanness, when really they’re just carrying more than we can see?

Further Reading

These works explore not only the history and science behind these topics, but also the human stories that lie beneath—stories like my mother’s.

● Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

● #1 Meyerowitz, J. (1994). Beyond the Feminine Mystique: A Reassessment of Postwar Mass Culture, 1946–1958. The Journal of American History, 79(4), 1455–1482.

● #2 Schreiber, L. (2013). Madness and Medicine: Mental Illness in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press.

● #3 Jones, S. H., & Ford, R. (2004). Bipolar disorder in women: diagnosis and management. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 8(3), 181–189.

Now I miss your Mom!